Did all the

common (non-samurai) people of Edo benefit from the earthquake?

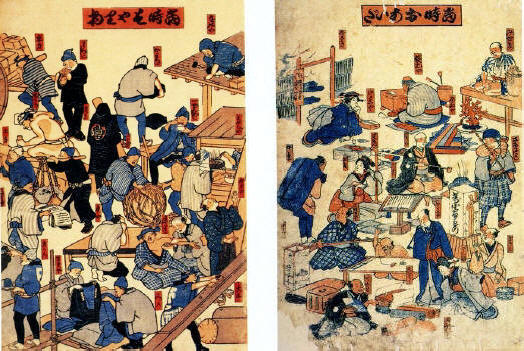

No. The first namazu-e on

this page is entitled Ō-namazu-go no namayoi

大鯰後の生酔い (Tipsiness following the great namazu

[=earthquake]). It depicts a large group, still somewhat disoriented, in the

immediate wake of the earthquake. The Kashima deity vigorously skewers the

namazu with a sword, and the huge fish, laid out on a table, divides the

print into upper and lower sections. The dozens of people depicted in the print

thus divide into two groups. Those at the top are “smiling,” while those at the

bottom are “weeping” and “have plenty of free time” that is, they are

unemployed. The smiling group includes a carpenter, a plasterer, a seller of

lumber, a blacksmith, a roof tile merchant, an elite courtesan, an ordinary

prostitute, a physician, and sellers of certain types of foods that could be

eaten without preparation. In total, the print depicts about 30 specific

occupations as profiting from the earthquake. The crying group includes a

teahouse proprietor, a seller of eels, a variety of entertainers such as

musicians, comedians, and storytellers, a seller of luxury goods, a diamond seller, and a seller of

imported goods—25 specific occupations in all. Other namazu-e taking up

the theme of society divided along the lines of winners and losers portray similar

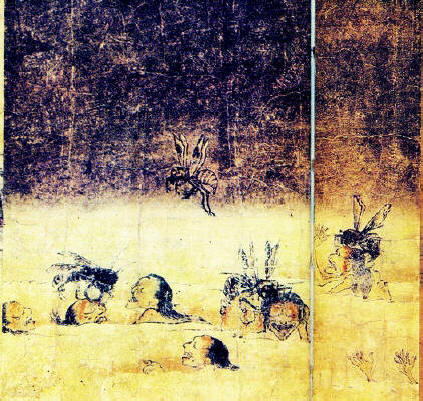

sets of occupations, though the elite courtesan sometimes ends up in the “idle” category (the second image on this page is an example: winners on the

left, losers on the right). Notice the social complexity of Tokugawa urban

society as expressed in a wide variety of specialized occupations.

No. The first namazu-e on

this page is entitled Ō-namazu-go no namayoi

大鯰後の生酔い (Tipsiness following the great namazu

[=earthquake]). It depicts a large group, still somewhat disoriented, in the

immediate wake of the earthquake. The Kashima deity vigorously skewers the

namazu with a sword, and the huge fish, laid out on a table, divides the

print into upper and lower sections. The dozens of people depicted in the print

thus divide into two groups. Those at the top are “smiling,” while those at the

bottom are “weeping” and “have plenty of free time” that is, they are

unemployed. The smiling group includes a carpenter, a plasterer, a seller of

lumber, a blacksmith, a roof tile merchant, an elite courtesan, an ordinary

prostitute, a physician, and sellers of certain types of foods that could be

eaten without preparation. In total, the print depicts about 30 specific

occupations as profiting from the earthquake. The crying group includes a

teahouse proprietor, a seller of eels, a variety of entertainers such as

musicians, comedians, and storytellers, a seller of luxury goods, a diamond seller, and a seller of

imported goods—25 specific occupations in all. Other namazu-e taking up

the theme of society divided along the lines of winners and losers portray similar

sets of occupations, though the elite courtesan sometimes ends up in the “idle” category (the second image on this page is an example: winners on the

left, losers on the right). Notice the social complexity of Tokugawa urban

society as expressed in a wide variety of specialized occupations.

Although the earthquake

has divided this society, it has also brought it together. In Ō-namazu-go

no namayoi, the people on each side of the namazu are dressed similarly

and assume similar postures. The winners are not celebrating, and everyone looks

more dazed than anything else. The earthquake has united them in a common

terrifying experience. Certainly the sellers of luxury goods, for example, will

suffer from the diversion of money to such basics as building supplies and

constructing work. There is no suggestion in this print, however, of censure or

that those on the crying side of the namazu deserve any sort of cosmic

punishment. Instead, the earthquake is an example of the instability of the

material world, a basic tenet of Buddhism. Those on the losing side of the

namazu deserve compassion and assistance—a point to keep in mind when

looking at the third image on this page.

Although the earthquake

has divided this society, it has also brought it together. In Ō-namazu-go

no namayoi, the people on each side of the namazu are dressed similarly

and assume similar postures. The winners are not celebrating, and everyone looks

more dazed than anything else. The earthquake has united them in a common

terrifying experience. Certainly the sellers of luxury goods, for example, will

suffer from the diversion of money to such basics as building supplies and

constructing work. There is no suggestion in this print, however, of censure or

that those on the crying side of the namazu deserve any sort of cosmic

punishment. Instead, the earthquake is an example of the instability of the

material world, a basic tenet of Buddhism. Those on the losing side of the

namazu deserve compassion and assistance—a point to keep in mind when

looking at the third image on this page.

Other than a clear

disdain for the extremely wealthy members of society, the 1855 namazu-e

do not reflect any strong sense of class antagonism. Even though, for example,

sellers of Chinese imported goods suffered as a result of the earthquake, no

namazu-e celebrates their plight. As we have seen, many namazu-e do

celebrate the newly-acquired wealth of those workers who have profited from the

earthquake, and the overall impression from the prints in total is that the

earthquake was a terrifying but necessary medicine to rectify a sick society.

Even this point, however, is not without ambivalence. In addition to the death

and destruction of the earthquake itself, some namazu-e are clearly

critical of the newly-rich construction trades workers and others who have

benefited from the earthquake. The message is not so much that they do not

deserve the economic benefits that have come their way, but that they should not

flaunt their wealth while others fellow commoners in different occupations are

still suffering.

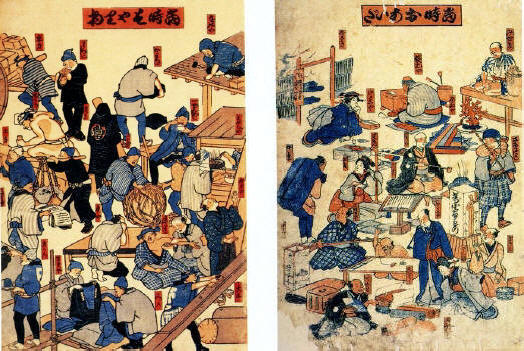

Nangichō

難儀鳥 (Hard-to-figure-out

bird) is a good example of namazu-e critical of the newly-rich (third

image on this page). In this print, five tradesmen are sitting around a

namazu in an expensive restaurant. The namazu is going to be their

feast during a night of drinking and revelry. A giant bird, however, swoops down

and snatches the namazu away from them. The reason that the bird is “hard

to figure out” is that it consists entirely of tools and objects from

occupations adversely effected by the earthquake. Its tail feathers are oars

for small boats, and its wings are books, dry goods, abacuses, and tall geta

shoes. Its neck and crown are the hairpins of elite courtesans and tea ceremony

whisks. In other words, the bird represents such professions as tea ceremony

teachers, courtesans, and small boat operators. It also includes booksellers,

pawn shops, and clothing stores. The basic message: members of occupations

profiting from the earthquake should at least have the decency to refrain from

public displays of wealth while others are suffering.

Incidentally,

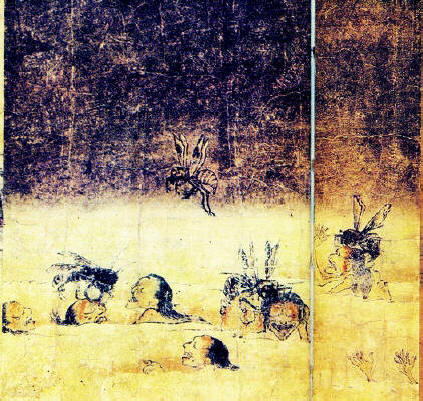

The broader theme of insensitivity to the suffering

of others is common in Buddhism generally and in popular Japanese visual art.

One of the best examples is a scene from a medieval picture scroll depicting

Buddhist hells. One of these hells is “the place of puss and blood” (nōketsusho),

into which fall “those who in a previous life, owing to delusions of stupidity,

offered foul or polluted things to others as food.” In the depiction of this

hell in the Jigoku-zōshi (Hell picture scroll), sinners swim in a

giant vat of puss while melon-sized giant wasps descend from time to time to

sting  their

exposed heads (see the last image on this page). A woman in the foreground is

pointing at another woman being stung by a wasp and laughing at this sufferer’s

misfortune. The laughing woman seems oblivious to the wasp that is about to descend

onto her own head.

their

exposed heads (see the last image on this page). A woman in the foreground is

pointing at another woman being stung by a wasp and laughing at this sufferer’s

misfortune. The laughing woman seems oblivious to the wasp that is about to descend

onto her own head.

No. The first namazu-e on

this page is entitled Ō-namazu-go no namayoi

大鯰後の生酔い (Tipsiness following the great namazu

[=earthquake]). It depicts a large group, still somewhat disoriented, in the

immediate wake of the earthquake. The Kashima deity vigorously skewers the

namazu with a sword, and the huge fish, laid out on a table, divides the

print into upper and lower sections. The dozens of people depicted in the print

thus divide into two groups. Those at the top are “smiling,” while those at the

bottom are “weeping” and “have plenty of free time” that is, they are

unemployed. The smiling group includes a carpenter, a plasterer, a seller of

lumber, a blacksmith, a roof tile merchant, an elite courtesan, an ordinary

prostitute, a physician, and sellers of certain types of foods that could be

eaten without preparation. In total, the print depicts about 30 specific

occupations as profiting from the earthquake. The crying group includes a

teahouse proprietor, a seller of eels, a variety of entertainers such as

musicians, comedians, and storytellers, a seller of luxury goods, a diamond seller, and a seller of

imported goods—25 specific occupations in all. Other namazu-e taking up

the theme of society divided along the lines of winners and losers portray similar

sets of occupations, though the elite courtesan sometimes ends up in the “idle” category (the second image on this page is an example: winners on the

left, losers on the right). Notice the social complexity of Tokugawa urban

society as expressed in a wide variety of specialized occupations.

No. The first namazu-e on

this page is entitled Ō-namazu-go no namayoi

大鯰後の生酔い (Tipsiness following the great namazu

[=earthquake]). It depicts a large group, still somewhat disoriented, in the

immediate wake of the earthquake. The Kashima deity vigorously skewers the

namazu with a sword, and the huge fish, laid out on a table, divides the

print into upper and lower sections. The dozens of people depicted in the print

thus divide into two groups. Those at the top are “smiling,” while those at the

bottom are “weeping” and “have plenty of free time” that is, they are

unemployed. The smiling group includes a carpenter, a plasterer, a seller of

lumber, a blacksmith, a roof tile merchant, an elite courtesan, an ordinary

prostitute, a physician, and sellers of certain types of foods that could be

eaten without preparation. In total, the print depicts about 30 specific

occupations as profiting from the earthquake. The crying group includes a

teahouse proprietor, a seller of eels, a variety of entertainers such as

musicians, comedians, and storytellers, a seller of luxury goods, a diamond seller, and a seller of

imported goods—25 specific occupations in all. Other namazu-e taking up

the theme of society divided along the lines of winners and losers portray similar

sets of occupations, though the elite courtesan sometimes ends up in the “idle” category (the second image on this page is an example: winners on the

left, losers on the right). Notice the social complexity of Tokugawa urban

society as expressed in a wide variety of specialized occupations. Although the earthquake

has divided this society, it has also brought it together. In Ō-namazu-go

no namayoi, the people on each side of the namazu are dressed similarly

and assume similar postures. The winners are not celebrating, and everyone looks

more dazed than anything else. The earthquake has united them in a common

terrifying experience. Certainly the sellers of luxury goods, for example, will

suffer from the diversion of money to such basics as building supplies and

constructing work. There is no suggestion in this print, however, of censure or

that those on the crying side of the namazu deserve any sort of cosmic

punishment. Instead, the earthquake is an example of the instability of the

material world, a basic tenet of Buddhism. Those on the losing side of the

namazu deserve compassion and assistance—a point to keep in mind when

looking at the third image on this page.

Although the earthquake

has divided this society, it has also brought it together. In Ō-namazu-go

no namayoi, the people on each side of the namazu are dressed similarly

and assume similar postures. The winners are not celebrating, and everyone looks

more dazed than anything else. The earthquake has united them in a common

terrifying experience. Certainly the sellers of luxury goods, for example, will

suffer from the diversion of money to such basics as building supplies and

constructing work. There is no suggestion in this print, however, of censure or

that those on the crying side of the namazu deserve any sort of cosmic

punishment. Instead, the earthquake is an example of the instability of the

material world, a basic tenet of Buddhism. Those on the losing side of the

namazu deserve compassion and assistance—a point to keep in mind when

looking at the third image on this page.

their

exposed heads (see the last image on this page). A woman in the foreground is

pointing at another woman being stung by a wasp and laughing at this sufferer’s

misfortune. The laughing woman seems oblivious to the wasp that is about to descend

onto her own head.

their

exposed heads (see the last image on this page). A woman in the foreground is

pointing at another woman being stung by a wasp and laughing at this sufferer’s

misfortune. The laughing woman seems oblivious to the wasp that is about to descend

onto her own head.